On the morning of January 24 1788, two French frigates, the Astrolabe and La Boussole, stood in towards the sheer cliffs of New Holland and made their way along the coast to Botany Bay. There, on the far side of the world, after being at sea for two and a half years, they encountered a sight they had not seen for many months: a fleet of ships, moored at the bottom of the bay. The French had anticipated finding some kind of British colony in New Holland. On the other hand, the British fleet of eleven ships sitting at the bottom of the bay were no doubt startled by the sudden appearance of two warships so far out in the middle of nowhere. The British soon discovered that the French frigates were part of a voyage of exploration commanded by Jean-François de Galaup, Comte de La Pérouse.

La Pérouse had arrived off the coast of New Holland after having successfully sailed halfway across the world. From the port of Brest they rounded Cape Horn, sailed up the coast of Chile, turned westward towards Easter Island and then onward to the Sandwich Islands. Alaska, California, Macao, Korea, Russia and Japan – the expedition seemed to land everywhere one could possibly land in the Pacific Ocean, creating maps, taking specimens and making contact with the local people along the way. On the 6th of December 1787, in search of fresh water and fresh food to deal with a potential outbreak of scurvy, the expedition arrived at the island of Tutuila in present-day American Samoa. Five days later, after having made their water and awaiting high-tide to float their boats, the local Samoans suddenly attacked. By the time they were able to shove off from shore and return to the ships, twelve of the expedition’s men were dead, including the captain of the Astrolabe, and many more seriously wounded.

After limping into Botany Bay, they set up a small camp to regroup and rest from the devastating events of the previous month. Meanwhile, the British fleet relocated to Port Jackson to the north in search of better land and a deeper harbour. Then, on the 10th of March, La Pérouse gave the order to weigh anchor and set sail for New Caledonia. They were never heard from again.

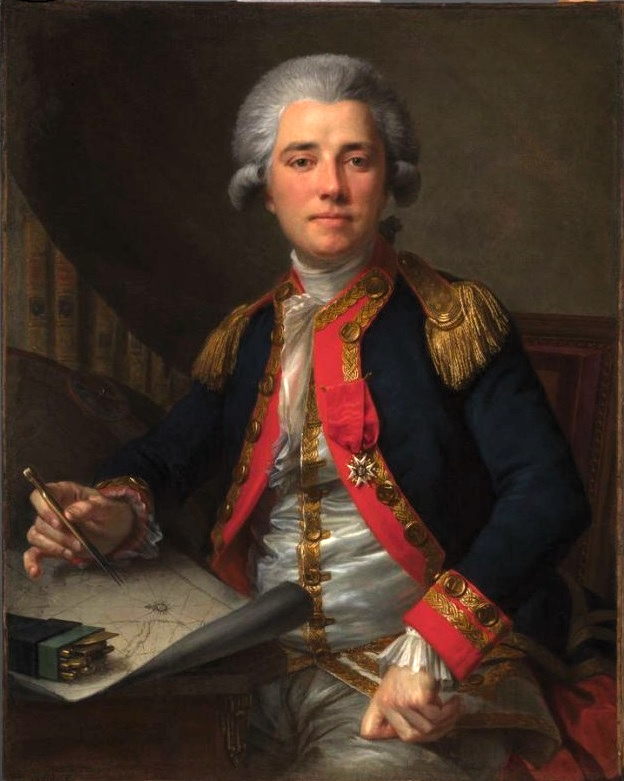

La Pérouse embodied the vibrance of the mid to late 18th century like few had before him – he was modern, scientific, quick-thinking, daring, controversial and above all else he was nobility. As a young man, records show that he got himself into trouble here and there. As a seaman and navigator, he outshone his peers in the French Navy. La Pérouse was the perfect choice to finish what James Cook, the navigator who had blazed the trail of Pacific exploration the decade prior, had started. In fact, it was Louis XVI himself that instructed La Pérouse on the direction of the expedition and goals of the mission itself. It wasn’t until forty years after La Pérouse and the expedition had vanished that the nation of France was able to get some closure on the loss of one of their most competent and respected mariners. Swords and other artifacts had been found scattered throughout the people of the Santa Cruz Islands, and were confirmed to have been owned by members of the La Pérouse expedition when they were brought back to Europe.

La Pérouse began his long-lasting relationship with the ocean when he joined the French Navy as a garde-marine (or midshipman) in the port of Brest in 1756. A year later, he received his first posting to Le Célèbre, a 64-gun ship that had only recently been launched and was being fitted out to join the squadron under the command of Emmanuel-Auguste de Cahideuc, Comte Dubois de la Motte. Luckily for La Pérouse, it was his own cousin1, Clément de la Jonquière, in command. In early May, La Pérouse and the squadron of nine ships and two frigates left Brest, slipped past the British blockade during inclement weather and began the long North Atlantic crossing, bound for his first oversea port of call – Louisbourg.

The year of 1757 was one of the busiest that the port of Louisbourg had ever seen. In response to the combined threat of a land assault and Sir Francis Holburne’s fleet operating out of Halifax, three French squadrons had been ordered to rendezvous at Louisbourg: De Bauffremont’s squadron reached Louisbourg on the 31st of May, Du Revest’s arrived the 19th of June and Dubois de la Motte’s ships dropped anchor on the 20th of the same month – a grand total of eighteen ships-of-the-line and close to 10,000 seamen2. The officers and seamen would spend the late spring and early summer alternating between constructing defensive works up and down the coast of Cape Breton and no doubt partaking in some shore leave3. John Dunmore in his book Where Fate Beckons: The Life of Jean-François de la Pérouse says of La Pérouse’s time in Louisbourg: “Jean-François received a warm personal welcome from the governor, Augustin de Drucourt, who had once been in charge of the Brest École des Gardes and who was always pleased to welcome any of the young gardes who chanced to land in Louisbourg. Although busy with his duties, he saw that La Pérouse was shown around and well looked after during his brief stay.”

It was in these very waters that as an officer-in-training, La Pérouse would begin to make the transition from the theory of mathematics, navigation, astronomy, and cartography to its application through sailing, log-keeping, dead-reckoning and noon sightings. For someone’s first time at sea, these first few months must have been vivid and engrossing – hours were replaced with bells, beds replaced by hammocks and one’s usual diet with shipboard victuals.

A year later, midshipman La Pérouse was back in the waters off Cape Breton, this time serving aboard the frigate Zéphyre under Captain de Ternay4. Attached to Du Chaffault de Besné’s squadron of five ship-of-the-line and four smaller ships, they had raced to Cape Breton from Rochefort during the month of May 1758, intent on slipping into Louisbourg harbour before Sir Edward Boscawen’s immense fleet began their blockade of the port and subsequent landing of troops. After a remarkably fast Atlantic crossing, Du Chaffault and the squadron finally dropped anchor in Ste Anne’s only to discover that the British fleet had been spotted off of Louisbourg earlier that very day. They were too late. While two officers raced towards Louisbourg to inform the governor of their arrival, the squadron began disembarking the Cambis regiment, which proceeded overland towards the fortress of Louisbourg from Spanish Bay. Ten days later, as the squadron was standing off of the Ciboux Islands at the mouth of Ste Anne’s Bay awaiting orders, they finally received word from Governor Drucour at Louisbourg to not attempt to force their way into the harbour. Louisbourg surrendered a month and a half later.

Twenty years later in 1781, we find La Pérouse again in the waters off of Cape Breton, but in circumstances much altered by the ebb and flow of power and politics. By this time, La Pérouse is a frigate captain, Cape Breton is now a British holding, and France is allied with the Americans in their fight for independence. One can’t help but wonder if he brought his ship in towards Louisbourg Harbour to take a look at what was left of the old fortress after it had been dismantled by the British twenty years earlier.

It’s been said that on the day of his execution, Louis XVI asked, “any news of La Pérouse?” The answer is the same today as it was back then. In the last few years, positive identifications have been made on the wrecks of the Astrolabe and La Boussole, having come to rest on the shoals of Vanikoro in the Santa Cruz Islands, but the final resting place of La Pérouse and the rest of the expedition still remains a mystery. For now, the answers remain locked away in the vault of time.

_____________________________________________________________________________

1 Some sources identify de la Jonquière as La Pérouse’s uncle, not his cousin.

2 J.S. McLennan. Louisbourg from it’s Foundation to its Fall, 1713 -1758. MacMillan, 1918. p.203

3 According to the thesis Popular Culture and Public Drinking in Eighteenth Century New France: Louisbourg’s Taverns and Inns 1713 – 1758, there were “twenty-eight permanent (drinking establishments) between 1748 and 1758” in Louisbourg.

4 D’Arsac de Ternay would go on to command the Expedition particulière in 1780, bringing French military support under the Comte de Rochambeau to Rhode Island during the American Revolution. La Pérouse would serve under de Ternay as captain of the Amazone during the expedition.